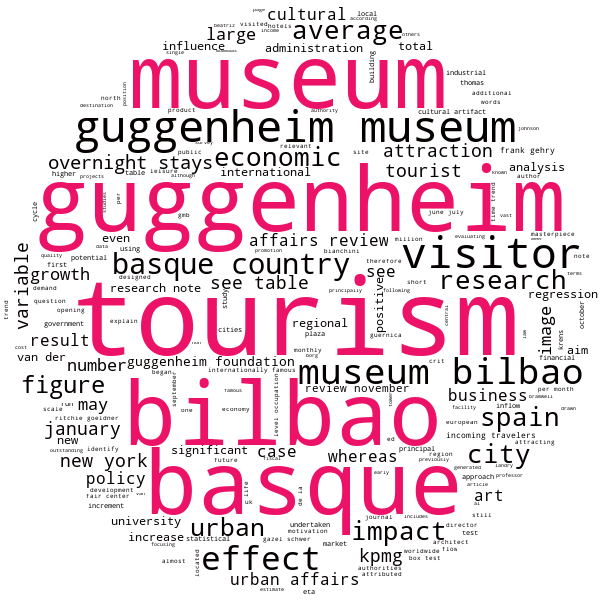

| Keyword | Number of occurrences | Frequency | Extractor string |

|---|---|---|---|

| basque | 31 | 0.16 | maui |

| bilbao | 47 | 0.25 | maui |

| guggenheim | 51 | 0.27 | maui |

| museum | 42 | 0.22 | maui |

| tourism | 38 | 0.20 | maui |

No results.

No results.

RESEARCH NOTE

EVALUATING THE INFLUENCE OF A LARGE CULTURAL ARTIFACT IN THE ATTRACTION OF TOURISM The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao Case

BEATRIZ PLAZA

University of the Basque Country, Spain

Bilbao is an outstanding test case for the impact of an internationally famous cultural facility in a context that otherwise does not lend itself to large flows of tourism. Although early for a com-plete impact study, the aim of this study is to quantify the influence of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in the attraction of tourism and to identify the potential factors that explain such impact in the short run.

Large-scale internationally famous cultural artifacts, such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris, the Sydney Opera House, and the Statue of Liberty operate as central tourist attractions, becoming symbols of their respective cities. There is, however, no statistical estimate dealing with the impact of a single large-scale cultural artifact and its contribution to tourism (Landry and Bianchini 1995). The aim of this article is to verify the effect the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao plays in the growth of tourism. We are in a position to assert that Bilbao is an outstanding test case for the impact of a single internation-ally famous facility, considering that Bilbao was not previously known for its tourism potential, in a context that otherwise does not lend itself to large flows of tourism.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: I am profoundly indebted to Professor Roberto Velasco (University of the Basque Country–Spain), AulaNet (University of Oviedo-Spain), and Rocio G. Davis (University of Navarre–Spain) who kindly read an early draft of the article.

URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW, Vol. 36, No. 2, November 2000 264-274 © 2000 Sage Publications, Inc.

264

RESEARCH NOTE 265

Literature on impacts of attractions is vast, differing in complexity and costs (for methodology of tourism research, see Mommaas et al. 1996; Ritchie and Goeldner 1994). The macroeconomic approach includes research into effects on arrivals and overnight stays, balance of payment, effects on income, and employment, principally using multiplier and input-output analysis (Johnson and Thomas 1992; Law 1993; Van Den Berg, Van Der Borg, and Van Der Meer 1995; Gazel and Schwer 1997), cost-bene-fit analysis of projects in terms of fiscal impact (Gazel and Schwer 1997), and changes in life quality, among others. Microeconomic studies prefer a more customer-oriented approach principally using interviews, survey methodolo-gies, and segmentation techniques to identify the urban market (Page 1995; Jansenverbeke and Vanrekom 1996; Bramwell 1998).

Following the survey approach, KPMG Peat Marwick prepared some sta-tistics on tourism in Bilbao in a report for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (KPMG 1998). The consultant analyzed the replies of 1,208 questionnaires to visitors held in June and July 1998 to identify their origin and motivations. According to the results, 57% of the visitors to the Guggenheim traveled from non-Basque territories, and almost 84% signaled the Guggenheim as their principal destination. In other words, according to KPMG, in June and July 1998, the museum generated a new inflow of 97,525 persons of the total 261,383 who visited the Basque Country.

Here one observes the impact of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in the number of visitors and overnight stays, using monthly data from January 1994 to January 2000. The statistical data concerning the museum are drawn from the Guggenheim Foundation Bilbao, whereas the number of visitors to the Basque Country and overnight stays are drawn from the Basque Govern-ment’s Statistical Authority.

FOCUSING ON TOURISM PROMOTION

The city of Bilbao is located in the north of Spain, a short distance from France. Spain’s largest port and fourth-largest city, the population of metro-politan Bilbao is 905,866. As the economic and financial capital of the Basque Country, Bilbao’s gross national product (GNP) per habitant is 95% of the European Union average and 120% of the average of Spain as a whole (see Figure 1).

Founded in 1300, Bilbao reached peak prosperity during the industrial revolution and remained Spain’s northern capital of steel and shipping up until 1975, when the recession struck and turned it into a decaying backwater.

266 URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW / November 2000

Figure 1: Spanish Regional Varieties

Between 1979 and 1985, almost 25% of the industrial jobs in metropolitan Bilbao were lost, and a relevant part of the economic structure deteriorated.

In the late 1980s, city authorities began to take the tourism industry seri-ously as a source of job creation that could fill the gaps left by declines in older industries. Image policy was also planned to have a positive effect on the reputation of Bilbao as a business center, with the principal aim of encour-aging the local entrepreneurs’ pride, undermined by both the economic crisis and the violence of the ETA (ETA is a terrorist group that demands separation of the Basque Country from Spain).

Local leaders in the 1980s had very little experience in marketing the city, which had few renowned cultural assets to attract leisure tourism (the Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts, the Archaeological-Ethnographic Museum, two sym-phonic orchestras, a theater, and two movie theaters) and unpleasant weather (the annual rainfall is about 1,500 liters per square meter). Moreover, the city lacked a positive image as a consequence of industrial depravation and the terrorism of the ETA.

Nor did the Basque authorities comprehend the tourism potential of the region before, either by improving the promotion of Guernica,1 the fine cui-sine of the Basque region, its natural setting, or even its proximity to

RESEARCH NOTE 267

Pamplona, the city of the fiesta par excellence, made famous by Ernest Hemingway.

Nevertheless, the perception of tourism in Bilbao as something new is deceptive. Industrialized cities have always attracted visitors from outside their immediate region because of business travel, retail, cultural and sports facilities, and the desire to see friends and relatives (see Figure 2). Still, lei-sure tourism was only 8% of the total movement in 1996, whereas visitors who came for professional reasons (business and exhibitions in the Interna-tional Fair Center) constituted 60%.

Promoted by the Basque administration and Bilbao Metrópoli 30—a private-public partnership—Bilbao began developing ambitious projects such as the futurist subway system designed by Norman Foster and the new Guggenheim Museum. The plan also includes a transportation hub designed by architects Michael Wilford and James Stirling, a new airport by architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava, and a vast waterfront development of parks, apartments, offices, and stores adjacent to the Guggenheim, designed by Cesar Pelli.

This program is being undertaken mainly by the regional administration. In fact, the Guggenheim becomes a symbol of Basque fiscal autonomy, a public investment made without recourse to central government funds. Inter-estingly, at the time the Basque administration and the Guggenheim Founda-tion New York began negotiations, Frank Lloyd Wright’s building in New York was being refurbished and the Guggenheim Foundation urged liquidity. This attests to the autonomic government’s financial capacity.

Paradoxically, there is an apparent dichotomy between the Basque gov-ernment’s cultural policy and the terms of its agreement with the Guggenheim. It is significant to note that the Department of Culture of the Basque Government has always been run by the nationalist party. The cul-tural policy of the regional institutions is characterized by a very clear consis-tent concern with Basque identity, embodied in efforts for the protection of both the Basque language and heritage (Gonzalez 1993). Surprisingly, the Basque administration became the first promoter of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, an American franchise, a museum financed and owned by the Basque administration but run by the Guggenheim Foundation.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao was intended to be the core attraction for tourism in a city not known for its tourist attractions in order to revitalize its economy. Therefore, the key question is the following: How much addi-tional tourism, if any, can be attributed to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao from its opening in October 1997? Tourist growth inflow to the Basque Country may be a result of the worldwide growth in tourism, the favorable business cycle, the dynamism of the International Fair Center of Bilbao, the increasing attractiveness of San Sebastian (previously the main leisure

268 URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW / November 2000

tourism destination in the Basque Country), or even the cease-fire declared by the ETA in September 1998, which ended in December 1999. We must delimit the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao effect.

EVALUATING THE

GENERATION OF TOURISM

First, results (see Figure 2) show that the number of incoming travelers to the Basque Country rose from the opening of the museum onwards (October 1997). Figures show an average increment of 31,453 incoming travelers per month, 10,381 of whom are foreigners (see Table 2)—that is, a significant 33%. The level of occupation of the hotels also is higher (see Table 2), having improved from a 37.8% average to a higher 46.6%.

Yet, all this positive effect could be attributed to the influence of the favor-able economic cycle in Western countries or the growing flow of tourism worldwide rather than to the museum. Therefore, several regressions are undertaken (see Table 1) in which the dependant variables—the number of incoming travelers, overnight stays, and level of occupation—are regressed against time trend (TREND), seasons,2 and the number of visitors to the Guggenheim (GMB), in which time trend is a proxy variable of alternative variables (business cycle, tourism upward trend, and dynamism of the Inter-national Fair Center). This analysis aims to distinguish the Guggenheim effect from others and validate KPMG’s estimates.

The Durbin-Watson and Lung-Box tests are used to check serial autocor-relation. Apparent autocorrelation may be caused by functional misspecification, either by the inappropriate functional form or by the omis-sion of a relevant explanatory variable (Crouch 1994). The fitted relation-ships are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

A visitor increase to the Guggenheim leads to a 0.175 increase in the num-ber of incoming travelers to the Basque Country. From the opening date of the museum, an average of 98,035 people visited it monthly (see Table 2), which generated an additional monthly average inflow of 17,156 visitors to the Basque Country (98,035 × 0.175). In other words, visitors to the Guggenheim account for 54% of the growth in tourism experienced by the Basque Country from October 1997 to January 2000—that is, 17,156 visitors out of the total 31,453 average increase per month (see Table 2). With regard to foreigners, the museum accounts for almost 44% of the growth, whereas the effect rises to 55% in the case of Spaniards (see Table 2).

These results modify those supplied by KPMG. Their results state that 97,525 visitors were due to the Guggenheim in June and July 1998, whereas

RESEARCH NOTE 269

Figure 2: Visitors to the Guggenheim, Incoming Travelers to the Basque Country, and Overnight Stays (January 1994-January 2000)

SOURCE: Basque Government’s Statistical Authority and Guggenheim Foundation Bilbao.

the regression attributes to the Guggenheim the inflow of 35,655 visitors.

KPMG’s study is biased upward.

As far as the overnight stays are concerned, a one-visitor increase to the Guggenheim leads to a 0.284 increment in the amount of overnight stays (see Table 1). This means that 27,842 overnight stays (98,035 × 0.284) of the total 55,459 average increment per month (see Table 2) are attributed to the museum, that is, a significant 50% of the growth. As a consequence, the level of occupation of the hotels has improved from a 37.8% average to a higher 46.6%. In the case of foreign tourism, the Guggenheim explains 42.7% of the increment, whereas the effect on the overnight stays of Spaniards rises to 58%.

Interestingly, occupancy indices are considerably higher for the top-end range of the hotels (85%), whereas the average level remains low (46.6%). This attests to the nature of tourism that Bilbao is generating. A significant portion of the museum attendees is concentrated in the upper end of the

270 URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW / November 2000

TABLE 1: Influence of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (GMB): Undertaken Regressions

t-test: degrees of freedom = 57; t-crit. 1% = 2.39. DW test for AR1: N = 72 and k = 2; dU 1% sig-nificance level = 1.53. Ljung-Box test for AR14: chi-squared(14) crit. 5% = 23.68. Ljung-Box test for AR17: chi-squared(17) crit. 5% = 27.58.

income scale and is therefore in a position to incur high expenses with the corresponding multiplying effects in the city.

In conclusion, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao exerts an important effect on the attraction of tourism. The relevant question is this: Why is the museum attracting tourism?

THE GUGGENHEIM

MUSEUM BILBAO’S ATTRACTION

Judging by the first evaluation undertaken by Thomas Krens, director of the Guggenheim Foundation New York, the principal motive that inspires tourists to visit the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is the magnetism of Frank Gehry’s building3 itself (Krens 1999).

TABLE 2: Calculating the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (GMB) Effect

January 1994 to September 1997.

October 1997 to January 2000.

Regressions in Table 1.

272 URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW / November 2000

Figure 3: Gehry’s Masterpiece

Intangible image effects cannot be valued reliably. However, there is a way to determine whether such externalities exist through the analysis of the phenomenon of sponsorship. Obviously, the principal aim of sponsorship is not beneficence. Sponsors expect favorable publicity to the value of the money that they put in, which in the long run will turn into financial results. In the case of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, the number of sponsors has risen; there were 61 in 1997, 103 in 1998, and 134 in 1999. The financial sup-port raised from businesses has increased from 409 million pesetas in 1997 to 668 million in 1998 and to 723 million pesetas in 1999. These figures denote the positive expectations the museum evokes.

The research demands an evaluation of additional motivations, such as the link between the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation New York. The Guggenheim brand denotes pres-tige. Still, the Guggenheim has already inaugurated a downtown branch in SoHo (New York) that failed to attract the expected attendance and has had to rent part of its ground floor to the Italian boutique Prada. Consequently, although helpful, the label Guggenheim may be insufficient under certain cir-cumstances. Nevertheless, the Solomon Guggenheim connection gave the Basque authorities access to the famed architect Frank Gehry, who would have otherwise been unavailable.

On the other hand, the Guggenheim link connects the Bilbao museum to the U.S. market. The consumed quantity of the Guggenheim image increases even more to the extent that its silhouette is conducted through North Ameri-can news agencies that enjoy a monopoly power worldwide. As Stigler and Becker (1977) pointed out, the utility derived from the consumption of art

RESEARCH NOTE 273

depends on the consumed quantity, as well as the ability to appreciate art, which in turn is a function of past consumption of art. In other words, the dif-fusion of Frank Gehry’s masterpiece’s image through printed and audiovisu-als means of communication is making the museum a fashionable imperative for tourists (Plaza 1999).

An additional motive may be the celebration of special exhibitions such as China 5000 Years, in which no less than 424,883 visitors attended from July to September 1998. This score can be compared to the 1998 total of 1,307,187 tourists who visited the museum in that year.

The agenda for future research requests a more market-segmented approach to delimit more accurately the influence of each motivation, includ-ing the role of tour companies, the efficiency of management, and the public-ity—all potential variables to explain the important growth in the number of tourists. Future studies may also enable us to determine why average stays are so short (1.8 days per visitor) and may shed light on the nature of tourist trade.

In conclusion, the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is having a significant positive impact on Bilbao due to the museum’s capacity for attracting tour-ists. However, we should raise the interesting question as to whether a large internationally famous cultural artifact of this type may be subject to the product life cycle. Furthermore, Frank Gehry could replicate this style else-where, as presumably will happen with the forthcoming Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan (Cash and Ebony 1999), perhaps causing Bilbao to lose its present advantage. Still, a masterpiece cannot be facilely reproduc-ible, not even by the author himself. Creativity is a highly elusive reality, even for the artists.

NOTES

Guernica is the symbolic heart of Basque nationalism. The Spanish Civil War brought Guernica fame as the Nazi bombers, on Franco’s request, launched the first-ever saturation-bombing raid against the civilian population. Picasso commemorated the massacre on a canvas that now hangs in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

Trend variable is defined as a linear time trend series, with the value 1 in January 1994, 2 in February 1994, and so on. Seasons variables are defined as lagged independent variables.

The building is not only unique but is also located in the appropriate place. The site, once occupied by an old factory, is unusual: Frank Gehry’s work sprawls underneath the Puente de la Salve, one of Bilbao’s busiest road bridges, ending in a tower of structural steel and stone. Para-doxically, the triangular site is the center of The Hole, the way the city is called locally because it sits in a valley between mountains. Located in the heart of Bilbao, besides the river Nervión, the building strengthens the image of the city’s past, rooted on the shipyards and steelworks, yet looks forward into the future through its innovative design. The same building in a different

274 URBAN AFFAIRS REVIEW / November 2000

site would transmit neither the strength nor the significance it communicates from Bilbao (see Figure 3).

REFERENCES

Bramwell, B. 1998. User satisfaction and product development in urban tourism. Tourism Man-agement 19 (1): 35-47.

Cash, S., and D. Ebony. 1999. Gehry Guggenheim for Manhattan? Art in America 87 (11): 160. Crouch, G. 1994. Guidelines for the study of international tourism demand using regression

analysis. In Tourism and hospitality research: A handbook for managers and researchers, 2d

ed., edited by J.R.B. Ritchie and C. R. Goeldner, 583-96. New York: John Wiley.

Gazel, R. C., and R. K. Schwer. 1997. Beyond rock and roll: The economic impact of the Grate-ful Dead on a local economy. Journal of Cultural Economics 21:41-55.

Gonzalez, J. 1993. Bilbao: Culture, citizenship and quality of life. In Cultural policy and urban

regeneration: The West European experience, edited by F. Bianchini and M. Parkinson,

73-89. Manchester, UK: Manchester Univ. Press.

Jansenverbeke, M., and J. Vanrekom. 1996. Scanning museum visitors: Urban tourism market-

ing. Annals of Tourism Research 23 (2): 364-75.

Johnson, P., and B. Thomas. 1992. Tourism, museums and the local economy: The economic

impact of the North of England Open Air Museum at Beamish. Avebury, UK: Aldershot.

KPMG. 1998. Impacto de las actividades de la Guggenheim-Bilbao Museoaren Fundazioa en Euskadi. Bilbao, Spain: KPMG Peat Marwick.

Krens, T. 1999. Conversation with Thomas Krens, director of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Connaissance des Arts 559:106-7.

Landry, C., and F. Bianchini. 1995. The creative city. London: Demos.

Law, C. 1993. Urban tourism: Attracting visitors to large cities. London: Mansell.

Mommaas, H., H. Van der Poel, P. Bramham, and I. Henry. 1996. Leisure research in Europe:

Methods and traditions. Wallingford: CAB International.

Page, S. 1995. Urban tourism. New York: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Plaza, B. 1999. The Guggenheim-Bilbao museum effect: A reply. International Journal of

Urban and Regional Research 23 (3): 589-92.

Ritchie, J.R.B., and C. R. Goeldner, eds. 1994. Travel, tourism and hospitality research: A hand-

book for managers and researchers. 2d ed. New York: John Wiley.

Stigler, G., and G. Becker. 1977. De gustibus non est disputandum. American Economic Review 67:76-90.

Van Den Berg, L., J. Van Der Borg, and J. Van Der Meer. 1995. Urban tourism: Performance and

strategies in eight European cities. Avebury, UK: Aldershot.

Beatriz Plaza is an associate professor of economic policy in the Faculty of Economics at the University of the Basque Country (Spain) and former director of the Basque Govern-ment’s Foreign Trade Qualification Program. She is author of “The Guggenheim-Bilbao Museum Effect: A Reply,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23 (3): 589-92, 1999. Her major current research interest is urban economic development, focusing on industrial policy, provision of business services, and image management.